- Details

-

Published: Tuesday, 14 December 2021 08:10

*ANDRES MCKINLEY - El Faro

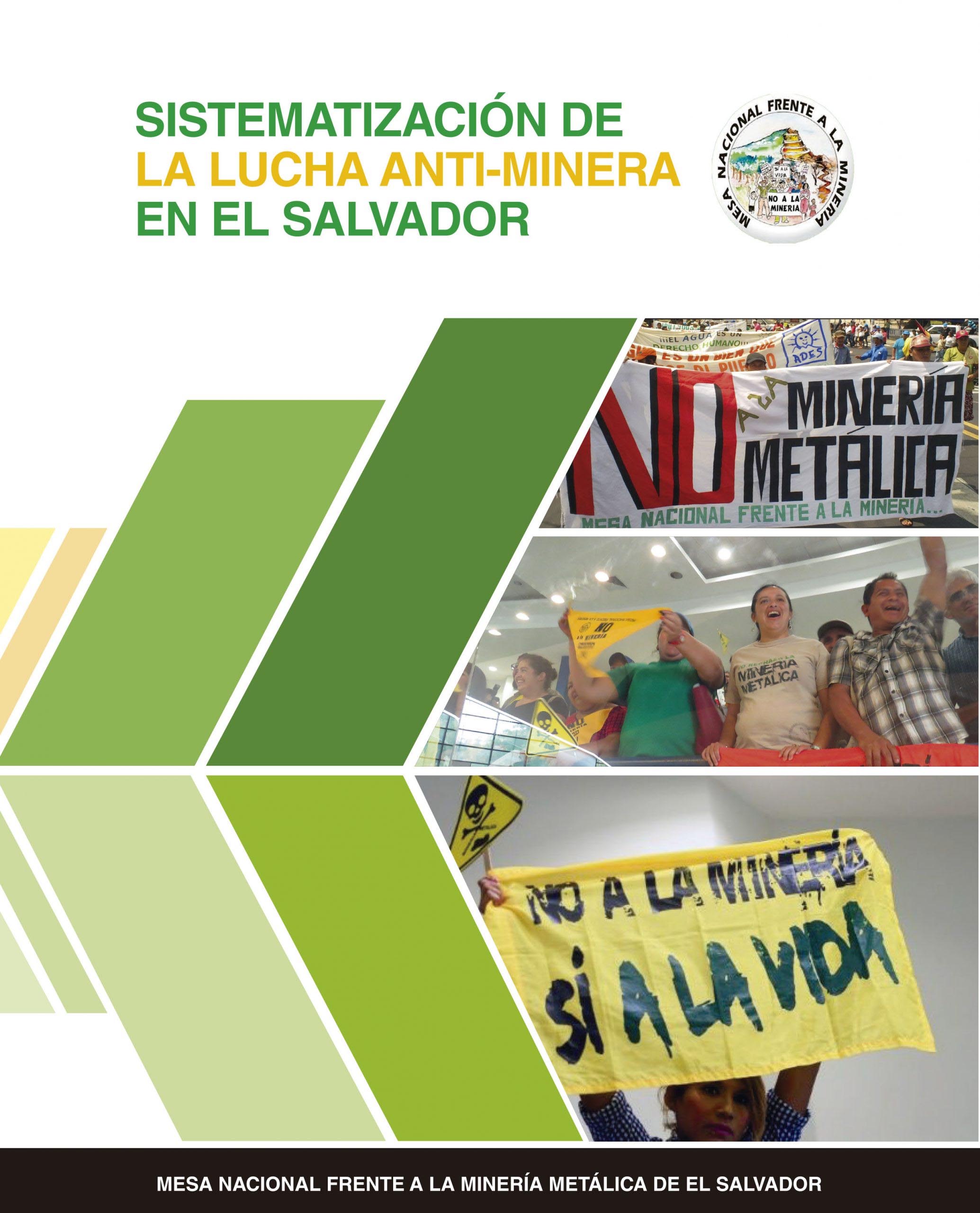

On March 29, 2017, the Salvadoran population celebrated with joy, hope and pride the approval of a law prohibiting metallic mining in all of its forms at the national level. This historic victory of a country known primarily for its worrisome levels of social violence, overpopulation, migration and environmental deterioration, rendered El Salvador the first nation in the world to responsibly analyze the high costs of metallic mining and exercise its right to say “No". Nevertheless, despite El Salvador's environmental vulnerability, the clear threat posed by metal mining and the strong and clear public rejection of this industry, there are worrying signs that suggest that the government of Nayib Bukele, with its puppet Legislative Assembly, are considering opening the door to metal exploration and exploitation again.

On March 29, 2017, the Salvadoran population celebrated with joy, hope and pride the approval of a law prohibiting metallic mining in all of its forms at the national level. This historic victory of a country known primarily for its worrisome levels of social violence, overpopulation, migration and environmental deterioration, rendered El Salvador the first nation in the world to responsibly analyze the high costs of metallic mining and exercise its right to say “No". Nevertheless, despite El Salvador's environmental vulnerability, the clear threat posed by metal mining and the strong and clear public rejection of this industry, there are worrying signs that suggest that the government of Nayib Bukele, with its puppet Legislative Assembly, are considering opening the door to metal exploration and exploitation again.

The government has shown little interest to date in environmental issues, and its policies and practices confirm the absence of an environmental conscience. Faced with the country's financial crisis, the current administration views metal mining as a potential source of income for a deeply indebted State, and it is widely known that the president maintains close relationships with large investors in this industry.

Instead of complying with the current law prohibiting metallic mining, the government, in May of this year, joined an international network of over 50 countries promoting mining called the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Metals and Sustainable Development and based in Ottawa, Canada. Two participants in the Forum, and members of the board of directors of the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM), were recently in the country to “promote debate on mining for sustainable development”, revealing a clear intention that threatens the interests of the Salvadoran people.

Even more worrisome is recent legislation creating the General Directorate of Energy, Hydrocarbons and Mines, approved by the Legislative Assembly on October 26 of this year with the objective of authorizing, regulating and supervising the operations of mining activities. The new law does not distinguish between metallic and non-metallic mining but refers only to mineral mining and establishes the promotion of mineral mining as a "duty of the State". It assigns the new Directorate with responsibility for establishing, maintaining and promoting cooperative relations with foreign and multilateral institutions or organizations "linked to the mining sector”; promoting the exploration of special areas where deposits with confirmed economic potential are located; and coordinating with the Ministry of the Environment in the assessment of mining and quarry exploration proposals.

The new law mentions only once the existing Law of Prohibition of Metallic Mining, stating that “the regulations, instructions, resolutions, standards, agreements and other general provisions […] will remain in force […] while they are not expressly repealed or modified”. This ambiguity clearly opens the door to renewed debate on metallic mining in El Salvador and threatens the guarantee of rights achieved with the ban of this industry in 2017.

The central issue in the debate on metallic mining in El Salvador has always been water, with the slogan "Yes to life, no to mining." It is widely recognized that El Salvador suffers from a water crisis of enormous proportions in terms of quantity, quality and access. According to experts, rivers are drying up, the water levels of the nation's most strategic aquifers are falling more than one meter per year, more than 90% of lakes and rivers are polluted and communities without access to this vital liquid, the source of all life, are taking to the streets.

Metal mining is a threat to water due to enormous consumption and contamination with toxic materials, such as cyanide (a chemical that can kill a human being in quantities less than a grain of rice), mercury, sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, lead, arsenic, cadmium, magnesium and other substances. According to an Oxfam America study, Dirty Metals, "When it comes to toxic emissions, metal mining is one of the leading industries."

Given this reality, broad based social coalitions, together with the Catholic Church, Protestant churches, the Office of the Attorney for the Defense of Human Rights, affected communities, environmental organizations, academic institutions, organizations of indigenous peoples and women and other important sectors of the population supported a bill presented on February 6, 2017 to ban metallic mining in the country. A survey conducted in 2015 by the Central American University, UCA, showed that 79.5% of participants considered El Salvador to be an inappropriate country for mining metals. In the same survey, 76% of those surveyed were opposed to the opening of mining projects in their municipalities; 77% believed that the Salvadoran State should definitively ban metallic mining in the country and, despite the critical situation of unemployment in the surveyed communities, 86% indicated that they had no interest in working in a mine.

Mining companies, to win hearts and minds, speak of new technologies for metallic mining more in harmony with the environment, using terms like "green mining," "modern mining," and "responsible mining." But the experience with metallic mining in Central America, and globally, teaches us that there is nothing new under the sun. Central American mines use more than a million liters of water daily. The Marlin mine in San Miguel Ixtlahuacán in Guatemala, considered by the World Bank as the most modern mine in Central America, used more than six million liters of water daily, the equivalent usage of a peasant family over a period of 30 years. A nickel mine on the shores of Lake Izabal in the same country uses thirteen times the amount of water required for the nearby town of El Estor daily. According to the residents of Valle de Syria in Honduras, the San Martín mine, in nine years of operations, dried up 19 of the 23 original rivers in the area. And in El Salvador, the Canadian mining company, Pacific Rim, in the exploration phase alone of its El Dorado project in San Isidro, Cabañas, dried up more than 20 historical community water holes.

Instead of acknowledging the depth of the water crisis and seeking lasting solutions, such as the approval of a General Water Law to assure good governance and a constitutional reform that recognizes water as a basic human right, the current administration continues to prioritize the interests of large companies over the interests of poor communities, approving projects that threaten sites for the recharging of strategic aquifers while water defenders in localities like Valle de Ángel in Apopa, the La Labor community in Ahuachapán and many others are accused of terrorism, persecuted and imprisoned.

Faced with all these worrisome realities, we are once again called to resist the advance of policies and practices, rejected in the past, that endanger the viability of our nation and the very life of our citizens.

-----------------

* ANDRES MCKINLEY: Has more than 50 years of experience working for sustainable development in Africa and El Salvador. He has a Masters degree in Health from the University of Florida, US and he currently works for the Central American University in El Salvador.

------------------

Translated from : https://elfaro.net/es/202112/columnas/25886/%C2%BFEstamos-frente-al-silencioso-regreso-de-la-miner%C3%ADa-met%C3%A1lica-en-El-Salvador.htm

Mongabay

Mongabay On March 29, 2017, the Salvadoran population celebrated with joy, hope and pride the approval of a law prohibiting metallic mining in all of its forms at the national level. This historic victory of a country known primarily for its worrisome levels of social violence, overpopulation, migration and environmental deterioration, rendered El Salvador the first nation in the world to responsibly analyze the high costs of metallic mining and exercise its right to say “No". Nevertheless, despite El Salvador's environmental vulnerability, the clear threat posed by metal mining and the strong and clear public rejection of this industry, there are worrying signs that suggest that the government of Nayib Bukele, with its puppet Legislative Assembly, are considering opening the door to metal exploration and exploitation again.

On March 29, 2017, the Salvadoran population celebrated with joy, hope and pride the approval of a law prohibiting metallic mining in all of its forms at the national level. This historic victory of a country known primarily for its worrisome levels of social violence, overpopulation, migration and environmental deterioration, rendered El Salvador the first nation in the world to responsibly analyze the high costs of metallic mining and exercise its right to say “No". Nevertheless, despite El Salvador's environmental vulnerability, the clear threat posed by metal mining and the strong and clear public rejection of this industry, there are worrying signs that suggest that the government of Nayib Bukele, with its puppet Legislative Assembly, are considering opening the door to metal exploration and exploitation again.

From tropical rain forests to drinkable water, a vast share of the planet’s essential environmental resources are found in developing countries. When growth-oriented governments and powerful Western corporations set their sights on these lands, or the minerals beneath them, local people standing in their way frequently find themselves bulldozed.

From tropical rain forests to drinkable water, a vast share of the planet’s essential environmental resources are found in developing countries. When growth-oriented governments and powerful Western corporations set their sights on these lands, or the minerals beneath them, local people standing in their way frequently find themselves bulldozed.