- Details

-

Category: FTAs & ISDS

-

Published: Thursday, 30 August 2012 11:32

Mining for Gold: A “Pact with the Devil”?

The economic crisis—and the rising price of gold—have spurred North American firms to reopen mines and attack environmental regulations. Here’s what we can learn from El Salvador’s moratorium on new mining permits.

by John Cavanagh, Robin Broad

Posted Aug 28, 2012

“The water‘s bright orange,” we exclaim while balancing ourselves precariously on rocks alongside a spring. We are visiting the community of San Sebastian in the province of La Union in the northeast corner of El Salvador. Above us stands a mountain with a prominent slash where U.S. and other firms mined gold for over a century, a mountain that also happens to be a key watershed for this area.

“I’ve seen this water also cranberry red and also bright yellow,” our companion responds. But then she quickly adds: “Remember: don’t touch the water. Last time I was here, I slipped and ended up with rashes all over my leg and stomach where I got wet.” She doesn’t need to remind us. Experts from the Salvadoran government’s Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources were here in July 2012 and they found levels of cyanide and iron that were through the roof.

What at first seems odd is that there hasn’t been commercial gold mining here for at least a decade—since the U.S. company Commerce Group left. But, as we learn on this, our second, research trip to El Salvador, a decade or two can be a blink of an eye for the environmental havoc wreaked by gold mining.

These ancient mountains contain not only gold and many other minerals, but also sulfide. It is a deadly combination with long-term consequences: once the mining excavations expose sulfide to the air and rain, it is converted to sulfuric acid. With each new rain, the acid unleashes new toxic substances down the mountain and into the springs and streams. In a nutshell: a long-term poisoning of the water, the land, and the people.

The now-orange spring water flows into a now-lifeless stream that flows into the San Sebastian river that, in turn, flows into the Santa Rosa river. Along the way, the water is used by many before it enters the Gulf of Fonseca far to the south and continues its journey.

The technical term for the environmental nightmare that is unfolding in front of us is "acid mine drainage.” Acid mine drainage has plagued mine sites from Pennsylvania to El Salvador for centuries. Mining expert Robert Goodland stresses that some communities near ancient Roman mines in England and Spain continue to suffer the effects of acid mine drainage over 2,000 years after the mines were closed. And remediation—or “clean up”—is technically and financially challenging. As a local college student who has studied the situation here explains: even if the funding were available, “we wouldn’t be able to clean this up even in 100 years.”

Read the full article here…

- Details

-

Category: Commerce Group

-

Published: Tuesday, 21 August 2012 09:57

¿De dónde sacó el dinero Commerce Group?

English Version

Lo último que se supo fue que la compañía minera de Milwaukee, Estados Unidos: Commerce Group, estaba esforzándose para conseguir los US $ 150,000 para pagar el proceso de apelación en el caso contra el Estado salvadoreño. Mientras se acercaba el día 19 de julio, fecha límite establecida por el Tribunal que está conociendo el caso, y Commerce Group no daba señales de poder pagar, parecía que el caso estaba, sin lugar a dudas, terminado.

Sin embargo, para sorpresa de aquellos que han monitoreado el caso, Commerce Group logró reunir el efectivo y pagó al Centro Internacional de Arreglo de Diferencias relativas a Inversiones (CIADI) el último día hábil, según informan funcionarios salvadoreños. Cuatro días después, el CIADI anunciaba que el caso se retomaba.

La pregunta que sobreviene es ¿De dónde sacó Commerce Group el dinero para continuar?

En noviembre de 2011 la compañía envió una carta al CIADI aduciendo que eran incapaces de pagar la relativamente pequeña garantía y además osaron en solicitar al CIADI que obligara al Estado salvadoreño a pagar los casi US $ 70, 000 de sus gastos, señalando que el Gobierno les debía dinero fruto de impuestos pagados en exceso y por un depósito por la renta de inmuebles. La compañía no ha reportado ningún ingreso desde el año 2002 y ha estado descendiendo en su nivel de gasto de operaciones a lo largo de los años, presumiblemente mientras sus finanzas disminuyen. Por lo tanto, si la compañía realmente está en situación desesperada que mencionan, y sus finanzas lo refuerzan ¿De dónde salió el rescate?

Commerce Group inició la demanda contra el Estado salvadoreño en 2009, demandando $100 millones de dólares en compensación de contribuciones a través de impuestos. Aunque la prueba científica es amplia, e incluye estudios recientes del Ministerio de Medio Ambiente que muestran la contaminación por cianuro y hierro en el agua local, Commerce Group argumenta que al negarle los permisos, el Gobierno salvadoreño está violando sus derechos de inversión. El caso ha llamado la atención internacionalmente como un ejemplo de los peligros de las cláusulas Inversor-Estado de los Tratados de Libre Comercio. La Coalición del Centro-Oeste de Estados Unidos contra la Minería Metálica llamó a la demanda “el cínico intento de una empresa fracasada de aprovecharse de Tratados Comerciales internacionales para hacer dinero que han sido incapaces de obtener por medios legítimos.

Una foto reciente del Sitio Abandonado de Commerce Group

- Details

-

Category: Commerce Group

-

Published: Friday, 17 August 2012 13:58

Where Did Commerce Group Get the Money?

Versión en Español

The last anyone had heard was that the Milwaukee based mining company Commerce Group was struggling to come up with the $150,000 to pay for the appeal proceedings in their case against the Salvadoran government. As July 19th, the payment deadline established by the tribunal hearing the case, drew closer and there was still no news of Commerce Group’s payment, it seemed that the case was all but over.

However, much to the surprise of those following the case, Commerce Group managed to scrape together the cash and paid the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) on the day of the payment deadline, according to government officials in El Salvador. Four days later the ICSID announced that the case would resume.

The question then becomes where did the Commerce Group get the money to continue?

In November of 2011 the company sent a letter to the ICSID claiming they were unable to pay the relatively small fee and even had the nerve to ask that ICSID force the Salvadoran Government to pay for almost $70,000 of their costs, claiming the Government owed them money from overpaid taxes and a security deposit on rented property. The company has not reported any income since the year 2002 and has been scaling down their operating cost over the years, presumably as their finances dwindle. Therefore, if the company really is in the dire straits that they claim and their finances seem to indicate, where did the last minute bail-out come from?

The Commerce Group began their suit against the Salvadoran Government in 2009, demanding $100 million in compensation from Salvadoran taxpayers. Even though there is ample scientific proof, including a recent study by the Ministry of the Environment showing cyanide and iron contamination in the local water, Commerce Group claims that the Salvadoran government is violating their rights as investors by denying them their permits. This case has drawn international attention as an example of the dangers of investor-state clauses in free trade agreements and the Midwest Coalition against Lethal Mining called the lawsuit “a cynical attempt by an unsuccessful company to exploit international trade agreements to make money which they have been unable to make by legitimate means.”

A Recent Photo of the Abandoned CG Mine Site

- Details

-

Category: Mining prohibition El Salvador

-

Published: Thursday, 09 August 2012 17:22

The Salvadoran Government Proposes Suspending Mining in El Salvador

On August 7th, the Ministry of the Environment (MARN) and the Ministry of the Economy (MINEC) presented a bill to the Legislative Assembly that would temporary suspend all mining activity in El Salvador. The bill states that there are not the necessary conditions for mining in El Salvador. If passed, the suspension would nullify all current mining permits, block the application for future permits and retroactively suspend all past permits. The bill references the Strategic Environmental Assessment, which was finally released at around the same time as the bill, as the basis for decision to suspend mining.

It is important to note that this bill is not the mining ban presented to the Legislative Assembly in 2005 by the National Roundtable against Metallic Mining (the Mesa in Spanish). The Minister of the Economy was citied a number of times in the press saying this would not mean a permanent ban on mining in the future. After reading through the bill it becomes clear that it no way guarantees there will not be mining in El Salvador, but instead identifies nine conditions that need to be met in order for mining to proceeding in the country. Among others, these conditions include gathering more scientific information about mining and its effects on the environment and water, strengthening the government institutions that would oversee mining activity, as well as the adequate closure of old mines and compensation for communities affected by past mining.

The bill establishes a committee of ten people appointed by the Technical Secretariat of the President’s Office which will be charged with monitoring the advances regarding the established conditions and eventually recommending that the suspension be lifted. Besides representatives of government institutions, this committee will include two “international experts,” two mining industry representatives and two representatives of civil society.

Below is the press statement from the Mesa regarding the proposed bill, but a few of the main reflections and critiques from El Salvador are:

1. The Funes government is fulfilling its promise to not allow mining, while simultaneously shifting the responsibility to the next administration in terms of making the final decision on the issue. After looking at the time frame established by the bill, it becomes clear that any analysis and decisions made regarding mining will happen after the 2014 elections.

2. The logic of the bill is flawed. If the conditions to ban mining are not present and environmental degradation and water scarcity are going from bad to worse in El Salvador, why not definitively take the necessary measures to assure the protection of water and natural resources in the future? Why establish conditions that seem difficult to meet instead of just banning mining?

3. The institutional weakness in El Salvador makes this bill extremely risky. The nine vague conditions laid out in the bill, as well as the fact that the President’s Office appoints the members of the committee that will make the proposal to revoke the suspension, means that if a pro-mining government were elected 2, 6, or 10 years from now, it would be relatively easy for them to claim the conditions have been met and stack the committee in their favor, essentially opening the door to mining, against the wishes of the communities and the general population. It is not unreasonable to think this could happen. Examples of policies being implemented that lack the necessary conditions to protect the population from their negative effects are a dime a dozen: privatization of public services, dollarization, the Central American Free Trade Agreement, etc.

4. If a bill were passed to ban mining it would need the votes of at least half the Legislative Assembly to be overturned, however with this bill seven people (of the committee of ten) can essentially decide to allow mining.

5. Passing this bill without changing or modifying Salvadoran Investment law will open the door to more law suits by international mining companies.

The National Roundtable against Metallic Mining States that the Law Proposed by the Government to Suspend Metallic Mining Activity is a False Solution and Calls on the Legislative Assembly to Definitively Ban Mining

In response to the proposed Special Law for the Suspension of Metallic Mining Exploration and Exploitation Projects Proceedings presented by the Salvadoran Government to the Legislative Assembly, we announce to the Salvadoran population and the international community that:

The suspension of metallic mining exploration and exploitation projects proposed by the Ministries of the Economy and Environment, does not eliminate the threat metallic mining poses to the country, it only postpones it. The bill, in its very nature, is temporary, superficial and does not contain any scientific basis. It shows that the government is not interested in banning metallic mining, even when we have scientifically demonstrated with technical arguments that metal extraction from Salvadoran soil is irrational because it would contaminate and destroy the environment, break down the social fabric in communities, as well as violate the fundamental rights of the population.

We reiterate that the serious environmental degradation our country suffers is incompatible with such a predatory industry, like that of metallic mining. The grave contamination that has affected 98% of our rivers, the chronic scarcity of potable water that population faces, as well as the fact that El Salvador is one of the most deforested and densely populated countries in Latin America and one of the most vulnerable countries in the world, where 98% of the population lives in areas prone to natural disasters, should all be reason enough to close the doors on mining companies in El Salvador.

As the National Roundtable against Metallic Mining we consider the proposed Law to Suspend Mining presented by the government a demagogic and false solution to the threats posed by vicious transnational companies from the extractive industry. If the Funes government really cares about guaranteeing sustainability and improving the quality of life of the population, instead of looking for a superficial solution that has been designed to save the administration itself, they should promote a ban on metallic mining through a new Mining Law that explicitly reflects the profound socio-environmental crisis we are suffering which is currently rapidly deepening.

Among other inconsistencies, we would like to point out that the proposal of creating a Follow-up Committee that will monitor the supposed “Institutional Strengthening Plan” and will judge when the suspension should be lifted, poses a threat to the Salvadoran population and particularly the communities that have been affected by mining projects. We denounce the fact that the decision to ban or allow mining falls on the shoulders of a small group of people. This should be a sovereign decision of the Salvadoran people that, according to the Constitutional values and International Law rhetorically referenced in the Suspension Law itself, that should be made by Salvadoran people together and not by a few businessmen and appointees named by the government in office at the time.

Government institutions have historically succumbed to the special interests of big business, whose only goal is to pillage our natural resources. This has been clearly shown by the destruction that metallic mining has caused in the San Sebastian River in the department of La Union and by the terrible lead pollution in the town of Sitio del Niño in La Libertad. This proves that the rules of the game, and the infamous institionality, tend to favor companies and that good intentions don’t really protect the majority of people and don’t promote dignified living conditions nor sustainability for the country.

For the reasons expressed above, we urge the Legislative Assembly not to be convinced by false solutions. Instead of spending time discussing the temporary suspension of metallic mining presented by President Funes, they should read, discuss, and pass as soon as possible the Law to Ban Metallic Mining which was presented by the National Roundtable against Metallic Mining in 2006.

We reject dangerous and false solutions!

We demand the immediate approval for a law that definitively bans metallic mining in El Salvador!

For a copy of the press release in Spanish see here.

For press coverage in Spanish of the government’s bill see La Prensa Graficia here, here and here; El Diario de Hoy here and here; Contrapunto, the Diario CoLatino, and La Pagina.

For press coverage of the Mesa’s response see the Diario CoLatino.

For a copy of the bill in Spanish see here.

- Details

-

Category: Mining prohibition El Salvador

-

Published: Wednesday, 18 July 2012 08:26

Mining Ambition Impedes Environmental Justice

The National Roundtable against Metallic Mining and environmental organizations consider that by allowing mining in El Salvador, the repercussions for the environment would exceed the multi-million debt that the country currently faces in the lawsuit filed by Pacific Rim.

By Ivannia Serrano

Translated by Jan Morrill

Original in Spanish

The last UN UNDAC (United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination Office) report in 2011 revealed that El Salvador is among the top ten most vulnerable countries in the world. There has been a 30% loss of bio-diversity; it’s the most deforested country in American Continent after Haiti. It also has the least access to water in the Central American Region.

Luis Gonzalez, from the Climate and Energy Division of the UNES, says “we have water access of between 1700 and 1800 m³, when the Central American average is 10,000 m³. That means that we are below average.”

He adds that El Salvador has had a drop in water levels in its rivers over the last fifty years, except for the Acelhuate River, which has had an increased flow because it transports 600 tons of feces daily. Along these lines, there are water level studies that indicate that the majority of rivers will disappear been 1,600 and 1,200 years from now, and in the case of the Lempa River, the most strategic water resource in the country, between100 and 160 years.

Studies by the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) show that only 2% of the water in the country is in “good” quality category.

With respect to this situation, Gonzalez claims that mining is not feasible in El Salvador, because one of the main impacts on a national level that could be created by mining would be on the water.

According to technical and scientific studies the gold particles found in El Salvador are scattered in the soil, and in many cases are microscopic. For this reason, the only economically feasible method for extracting this gold from the rock is through leaching, a physiochemical process in which gold is separated from rock by adding cyanide.

A specialist in climate and energy, Luis Gonzalez, explained that the use of cyanide is very harmful. “Cyanide is a very toxic chemical, to the point where the amount of cyanide equivalent to a grain of rice can kill an adult human being. Also, the heavy metals released could be arsenic, selenium, and lead which are also pollutants and can be toxic.”

According to research done by the UNES, each mining project would use 40 tons of cyanide a day. This, like many heavy metals, is a bioaccumulator, which means that if it is not absorbed by the environment little by little it can accumulate in the soft tissues of human beings. Consequentially, it causes degeneration at the cellular level and is the root of a number of illnesses like kidney disease, migraines, impotency, infertility, fetal damage, etc.

According to research done by the UNES, each mining project would use 40 tons of cyanide a day. This, like many heavy metals, is a bioaccumulator, which means that if it is not absorbed by the environment little by little it can accumulate in the soft tissues of human beings. Consequentially, it causes degeneration at the cellular level and is the root of a number of illnesses like kidney disease, migraines, impotency, infertility, fetal damage, etc.

Most of the gold mining companies in the world are Canadian. In El Salvador, Pacific Rim has been at the forefront. Many other companies, like Minerales Morazan, are also subsidiaries of Pacific Rim. However, Gonzalez said “it’s a junior firm, which specializes, more than anything, in exploration and when the exploration is finished they sell the project to a larger company.”

Currently, Pacific Rim has an exploration permit. However, in response to government opposition, which has not given a the company mining exploitation permit, the company has filed a $120 million lawsuit against the country in the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes ICSID, arguing profit expropriation.

To date, the process remains open, and a law that bans mining is the only way to avoid the actions taken by mining companies and possible suits against the government. According to Gonzalez, as long as the process continues, Pacific Rim can increase the amount of the suit by arguing they are incurring procedural costs. Also, this forces the Salvadoran Government to pay huge amounts of money to the international lawyers that are defending their case. According to studies done by FESPAD there have been more than $5 million spent already.

However, for the UNES representative, Pacific Rim has acted in the same way as mining companies throughout the world. “They arrive in a community and begin to buy people off, to sponsor the patron saint festivals for the mayor’s office, school uniforms for the children, the give out some bags, medical or eye campaigns, and obviously they create the false promise of some type of employment, and what all this has caused in the department of Cabañas, one of the areas most affected by metallic mining, is that there are divisions in way people think.”

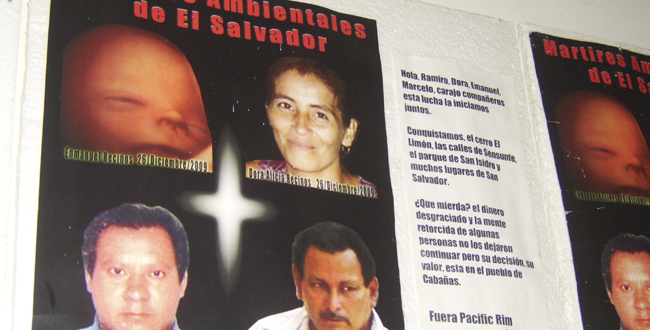

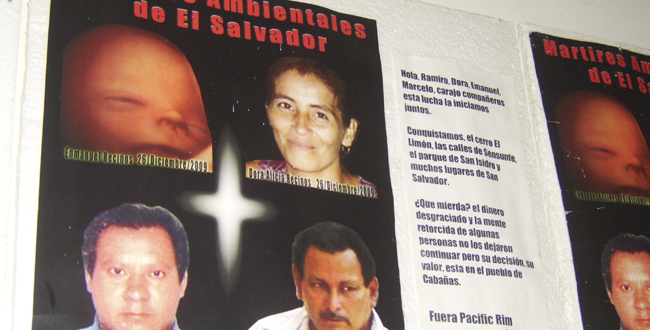

This idea is shared by Francisco Pineda, founder and president of the Environmental Committee of Llano de la Hacienda en Cabañas, who testifies that the deaths of five environmentalists in the area are the result of opposition by the population to mining at the “El Dorado” mine.

This idea is shared by Francisco Pineda, founder and president of the Environmental Committee of Llano de la Hacienda en Cabañas, who testifies that the deaths of five environmentalists in the area are the result of opposition by the population to mining at the “El Dorado” mine.

“The threats began when the communities became organized and to carry out direct action. Because of this, the company feels its investments are being threatened and it sued the government at the ICSID and that is when we began to receive more threats,” said Francisco.

Among the environmental leaders who were murdered, Dora Alicia Recinos stands out. She was 32 years old, a member of the Environmental Committee of Cabañas, and was 8 months pregnant when she died.

Juan Francisco Duran Ayala was most recent murder on June 24, 2011. Pineda describes him as a young man who studied foreign languages, and who could have helped with translating documents, because he was skilled. After his disappearance, he was found dead in Lamatepec with a gunshot wound to his head.

“To date we have not seen any investigations that clarify the facts in this case, and in the other cases, they say it was because of personal feuds,” says Pineda, who in 2011 received the Goldman Prize, one of the most recognized prizes on an international level, for his struggle against mining company Pacific Rim.

From his point of view, Pineda considers that a year after Juan Francisco´s the death, the Attorney General’s office has not been effective and its investigations it clings to its hypothesis and ignore the hypothesis that the population has proposed.

From his point of view, Pineda considers that a year after Juan Francisco´s the death, the Attorney General’s office has not been effective and its investigations it clings to its hypothesis and ignore the hypothesis that the population has proposed.

In this sense, he considers that his hypothesis should be taken into account and that not only should mining company representatives be investigated, but also legislative representatives, “there were close ties with mining companies during the elections. We believe that Pacific Rim has helped finance part of the political campaigns and that is why there is an agreement between them.”

In response to the issue, the mayor of San Isidro, José Bautista warns that the Legislative Assembly or the President of the Republic have the last word on whether mining will be approved or not. Also, he is close-lipped about the murders in his department.

Francisco Pineda, who has lost count of how many threats he has received in spite of protection given to him by the government, will not stop in the struggle to defend his land, the community and the country.

As part of the actions taken to defend natural resources in the country, the National Roundtable against Metallic Mining, presented an alternate document to the ICSID called an “Amicus Curiae” or Friend of the Tribunal. The idea in this process, according to Rodolfo Calles, the Roundtable facilitator, is “to present a number of arguments of why mining isn’t feasible in El Salvador to better illustrate our position against mining for the judges.”

To date, there has not been a response from the ICSID. For Rodolfo, this is because the majority of the arguments they presented are about human rights and the environment, which don’t represent weighty argument for this regulatory institution, because it is a predominantly trade-focused organization.

To date, there has not been a response from the ICSID. For Rodolfo, this is because the majority of the arguments they presented are about human rights and the environment, which don’t represent weighty argument for this regulatory institution, because it is a predominantly trade-focused organization.

Even so, the Roundtable is committed to continuing to provide support for the legal issues, and to continuing to provide proof and testimony of how mining affects the country. These efforts have been supported by international allies from the U.S. and Canada, including information campaigns to raise awareness in the public and to pressure Pacific Rim to drop their suit against the government.

Currently there are 25 exploration permit applications and 29 mining exploration concessions for gold and silver, which could in turn become 25 new law suits for the country, because there is still a national legal framework that does not ban mining as such.

For this reason, the National Roundtable proposes a law that would ban metallic mining. In the first place, to avoid more deaths in Cabañas because as long as there is a possibility for mining there will be opposition and violence. Secondly, to eliminate the threat of environmental degradation.

“Even if we loose the suit, it’s preferable to pay the 100 or 200 million, instead of allowing mining in El Salvador, because the environmental costs are much more than the amount of the suit” he claimed.

- Details

-

Category: Commerce Group

-

Published: Monday, 16 July 2012 18:00

The MARN confirms the presence of cyanide and iron in the San Sebastian River, La Unión

This weekend the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) confirmed the presence of unhealthy levels of cyanide and iron in the San Sebastian River, proposed mining site of the Milwaukee-based company the Commerce Group.

Below is a translation of the updates posted on the MARN website.

Here is the link to the MARN website.

Here are pictures of the pollution in the San Sebastian River.

La Unión, July 14, 2012.

The results of water samples taken by the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (MARN), which were collected two thousand five hundred meters from the bed of the San Sebastian River, in the area of the hamlet of El Comercio in Santa Rosa de Lima, confirmed the presence of cyanide and iron, among other substances.

The main source of contamination that was identified is a discharge of acid water that is rust colored following down from the higher ground on the Cosiguina mountain, an area where industrial mining was in operation for a number of decades.

The samples taken from various stretches of the river indicate that the contamination diminishes in concentration due to the increased water levels from the river during the rainy season. The MARN will carry out a similar study in the dry season to compare the impacts on this body of water.

There are a number of groups of individuals in the area who are mining on an artisanal scale, but it was ruled out that the quantities of cyanide and iron found in the runoff are related to these current practices.

At the petition of the Research of Investment and Trade Center (CEICOM), who associates the numerous causes of death in the locals of Santa Rosa de Lima with causes related to mining, the Vice-Minister of Environment and Natural Resources, Lina Pohl visited the hamlet of El Comercio this morning to see firsthand the investigations that the MARN was doing at the river.

The highest reading of cyanide found in the water flow was 0.450 milligrams per liter. The Salvadoran Compulsory Standard for Water for Human Consumption establishes a maximum limit of 0.05 milligrams per liter, which means that the quantities detected are nine times that amount.

Cyanide is a highly toxic substance for human beings and limits the development of aquatic life. This substance was used in the past in the mining process.

Another finding was high concentrations of iron. The highest reading of iron found was 393.4 milligrams per liter. For this substance, the Salvadoran Compulsory Standard for Water for Human Consumption establishes a maximum of 0.3 milligrams per liter. This means that the levels are over one thousand times the allowed limit.

During the last visit, MARN specialists, with the support of the Firefighters, opened two metallic containers that were left on private property used by the mining company.

In those containers 23 barrels and an un-determined number of bags with chemical substances, which were identified as sodium cyanide and ferrous sulfate, were found. Both of which are chemicals used in the gold extraction process. At this time, the stored materials do not represent a danger, even though they have potential for future danger.

After the tour of the mining area and visits to a number of points where springs of contaminated water begin their flow into the San Sebastian River further downstream, the Vice-Minister said “is is a very complex situation. We are finding a complicated relationship and history between the population and the exploitation of mining resources. This requires a comprehensive social-environmental vision.”

Vice-Minister Pohl stated that they will continue with the investigations of the pollution in the San Sebastian River and in establishing mitigation measures for the impacts caused in this body of water.

According to research done by the UNES, each mining project would use 40 tons of cyanide a day.

According to research done by the UNES, each mining project would use 40 tons of cyanide a day. This idea is shared by Francisco Pineda, founder and president of the Environmental Committee of Llano de la Hacienda en Cabañas, who testifies that the deaths of five environmentalists in the area are the result of opposition by the population to mining at the “El Dorado” mine.

This idea is shared by Francisco Pineda, founder and president of the Environmental Committee of Llano de la Hacienda en Cabañas, who testifies that the deaths of five environmentalists in the area are the result of opposition by the population to mining at the “El Dorado” mine. From his point of view, Pineda considers that a year after Juan Francisco´s the death, the Attorney General’s office has not been effective and its investigations it clings to its hypothesis and ignore the hypothesis that the population has proposed.

From his point of view, Pineda considers that a year after Juan Francisco´s the death, the Attorney General’s office has not been effective and its investigations it clings to its hypothesis and ignore the hypothesis that the population has proposed. To date, there has not been a response from the ICSID.

To date, there has not been a response from the ICSID.